Easter Vigil was two weeks away, and I still needed a confirmation name.

I had two criteria. First, someone who excelled where I struggled. My faith and compassion occasionally wane, a common issue for believers I imagine, and I will need course correction. And second, someone who appealed to seekers. At this moment, there is someone somewhere looking for the truth as I once did. When opportunities arise for me to share the faith, particularly in communities where the Catholic Church may not seem like a welcoming option, a saint from a non-traditional background may be best suited to stand by my side.

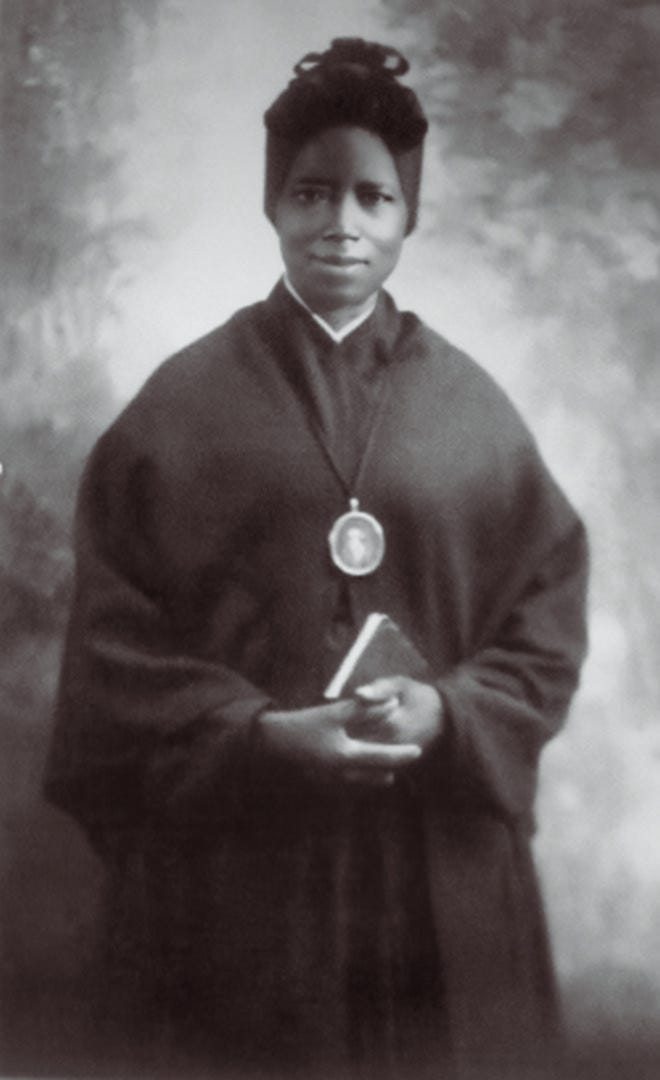

With just six days until my baptism and confirmation, I confidently settled on Saint Josephine Margaret Bakhita, the Sudanese-Italian sister of the Canossian order, canonized by Pope Saint John Paul II on October 1st, 2000.

Born in Sudan in 1869, Bakhita came from a prosperous family with three sisters and three brothers. At age seven, her life took a tragic turn when she was abducted by Arab slave traders. She was tortured, forcibly converted to Islam, and sold several times in the regional slave-markets. At the start of winter in 1888, God would lead her to Venice where she found fellowship with the Canossian Sisters. “Those holy mothers instructed me with heroic patience,” Bakhita recalled, “and introduced me to that God who from childhood I had felt in my heart without knowing who He was.”

I was reminded of my first weeks in the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults, and how welcoming and patient everyone was. I hadn’t entered a church since high school, and I still questioned the intentions of evangelists. Do they genuinely care about people, or are they like car salesmen trying to earn a commission from God? After working in Chicago for nearly two decades, I grew accustomed to deceit, greed, and hostility. Outside of a small group of friends, I hardly trusted or forgave anyone, and I had a surplus of animosity.

When I was a practicing Buddhist, I learned to turn my anger into equanimity, and my equanimity often slipped into apathy. From being immersed in toxic environments for so long, and centering myself over the humanity of my apparent foes, I was spiritually ailing. I didn’t see the man on Madison Street who randomly yelled profanities at me as a child of God, or even consider he was once a child. My attention was fixed on my own “enlightenment” rather than the larger picture around me.

Bakhita was asked how she would respond if she met her captors, and she promptly replied, “If I were to meet those who kidnapped me, and even those who tortured me, I would kneel and kiss their hands. For, if these things had not happened, I would not have been a Christian and a religious today.” I was taken aback by this response. At this point in my journey, prayer had significantly softened my disposition, but this kind of forgiveness was unfathomable. Despite all of the suffering Bakhita endured, she still came to receive and embody God’s grace. If she could do this, I could at least try to as well.

On May 17th, 1992, in a homily honoring Bakhita’s beatification, Pope Saint John Paul II said, “In Blessed Josephine Bakhita, we find an outstanding witness of God’s Fatherly love and a bright sign of the enduring value of the Beatitudes. In our time, when the race for power, money and pleasure causes distrust, violence and loneliness, the Lord is giving us Sister Bakhita as the Universal Sister so she may reveal to us the secret of the truest happiness.”

Saint Josephine Bakhita, pray for us!